Trusting Data Versus Trusting Your Gut

As if the CIO did not have enough to worry about; Cloud, Social, Mobile, along comes Data (BigData to be buzzword compliant). OK, I might have it a little backwards, Data has been a concern for a long time, but now, because of Cloud, Mobile and Social, Data is an even bigger challenge. The list of issues surrounding data is a long one; growth of, quality of, management of, storage of, interpretation of, access to and last but not least, analysis. Many of these are technological, but the real issue is when data crashes into a human…

Do You Trust Data or Do You Trust Your Gut?

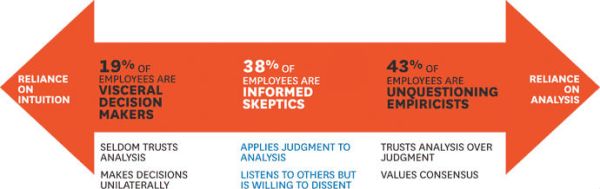

The stakes are real – the future of your business. Leveraged well, data will provide an edge, properly used it is a difference maker. Do phrases like: ‘My instincts got us here, and we are doing just fine’ or ‘it feels right’ fly around your office? Hyperbole, maybe, but most of us know the type and have experienced at least a bit of it. There is an argument that suggests that some people actually do know what the data says, and their ‘gut’ is right. As for the rest of us, I am not so sure, the answer is that balance is needed. According to HBR (Full source below), that balancing has a name – an informed skeptic:

At one end of the spectrum are the pure ‘trust your gut’ types on the other, the purists (“In god we trust, everyone else bring data”) types. The basis of the HBR article is: even if the data is good, decisions based on that data should be questioned – ie, be a bit of a skeptic. This is interesting and important.

“The ability to gather, store, access, and analyze data has grown exponentially over the past decade, and companies now spend tens of millions of dollars to manage the information streaming in from suppliers and customers.”

From my perspective, it is all about intelligence; using data, properly, to provide you and your business insights to make decisions. That is what you do, right; the data is there, everyone who needs it has access and the entire organization is leveraging it to its full potential? As the article also suggests, IT should spend more time on I, less on T – while it sounds fun, there is a small point there, not as big as the author makes it seem. To question data, to invite skeptics, everyone needs access

Do People Really Know What to Do with Data?

What are the reasons that data seems to scare people. Few will admit to being scared by data, but very few have the real background to argue on empirical terms when charts and graphs and conclusions are put in front of them. An IBM/MIT study (Source 3) identified three levels of analytical sophistication: Aspirational, Experienced and Transformed, in a Year-to-year comparisons of these groups (which can be seen in the source report) it shows that Experienced and Transformed organizations are increasing their analytical capabilities, significantly.

(note: The IBM/MIT report did not present the information in the format above, I used the article to create an image similar to the HBR article).

“The number of organizations using analytics to create a competitive advantage has surged 57 percent in just one year, to the point where nearly 6 out of 10 organizations are now differentiating themselves through analytics” IBM/MIT

What is unfortunate is that it sounds better than it really is. If you really start to dig deeper into the data (oh, the irony), the story is a bit more complex. While things are getting better, I am not sure I would characterize them as ‘good’. Out of curiosity, I wanted to look at a topic important to me, Customer Experience. Based on my interpretation of 3 sources of information, many know what to do, but are struggling to do it. By my read of the IBM/MIT report, only 1/2 ( 10%) of the organizations who ‘really get it’ (transformational) are using analytics to make decisions regarding customer experience. Turning that around, 90% are not, scary, unfortunate, reality.

“Typically, an organization’s highest-spending customers are the ones who take advantage of every channel, whether it’s the web, a mobile device, or a kiosk on a showroom floor.8 Unfortunately, these customers are most at risk for experiencing a disconnect in navigating channels that are not yet integrated. A unified multi-channel “bricks and clicks” approach can allow customers to move between website, smart phone app, or an in-store service counter with a consistent quality of engagement.” (Source 1)

The only way to know and really understand something like this is to have the data to prove it! It is not rocket science, but it does take some work. What steps are you taking to share data, train people and leverage what you have right there in front of you?

Conclusion

- Something as valuable as Data is not a Problem, it is powerful and valuable Asset,

- Help people to understand data, encourage them to be an educated skeptics (yes, question that Infographic)

- Gut Instincts are not bad, just keep things in perspective, right place right time,

- And for goodness sake, start using Data to better understand your Customers!

There is so much more to this story. In writing this post, I have a whole new level of respect for this topic…I hope you do too.

- Analytics in the Boardroom, IBM Institute for Business Value, Fred Balboni and Susan Cook

- Good Data Won’t Guarantee Good Decisions, Harvard Business Review, April 2012, Shvetank Shah, Andrew Horne, and Jaime Capellá

- Analytics: The Widening Divide How companies are achieving competitive advantage through analytics, MIT Sloan Management Review with IBM Institute for Business Value, David Kiron, Rebecca Shockley, Nina Kruschwitz, Glenn Finch and Dr. Michael Haydock

This post was written as part of the IBM for Midsize Business program, which provides midsize businesses with the tools, expertise and solutions they need to become engines of a smarter planet.

Hi Mitch

Another interesting post. But it left mw wondering whether it was about computing machinery, or about people. And about whether those same machines had taken over the madhouse.

Computing machinery is great at calculating the odds of anything. Like the sentient robot that saves the hero, Will Smith’s life in the film iRobot; by calculating the odds of his, versus a little girl’s survival in a sinking car and saving him. As Smith says in the film, a human wouldn’t have made that (wrong) decision. In contrast, humans are great at spotting patterns in unstructured data of the kind that computers wouldn’t know where to start with. Like the genius John Nash, played by Russell Crowe, in the film A Beautiful Mind; who scrawled formulae and data all over the walls and windows of his study to try and spot the patterns that ultimately led to his Nobel Prize for Economics winning work on Nash Equilibria.

Whether we like it or not, it is humans that make most decisions in life. As Daniel Kahneman – another Nobel Prize winning Economist – points out in his new book on ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’, we humans operate with two systems. A slow one, like a really, really slow version of computing machinery that we use for cognitively hard tasks like stochastic calculus, (go on try it for yourself) and a fast one that uses whatever data it has to hand to decide what to do next, like spotting the tabby cat slinking between the bushes in your garden. Quick as a flash. It is this ability that has allowed humans to survive in the pre-historical days of ‘do lunch or be lunch’. It should come as no surprise that about 95% of our decisioning is made by the fast system.

So what does big data mean for our natural tendency to think fast?

What you suggest is tantamount to providing lots of additional data in support of our slow system of thinking. Despite that fact that we have very limited bandwidth to absorb and make sense of this new data. And it doesn’t matter how much you pre-crunch the data, we humans are pretty rubbish at handling structured data of this kind. Not only that, we tend to mistrust people who are naturally better at crunching the data; calling them geeks, propellor-heads or much worse. They are not like us and we don’t trust them as a result.

So should we ignore big data as being effectively unusable?

Far from it. But perhaps rather than seeing big data as a way to put more structured data in front of decision makers we should think about using it in a different way, a visual way, to support their fast system of thinking across broad swathes of data. It is not for nothing that data visualisation is every bit as important as disseminating big data within organisations, even those bought into big data as much as IBM. This plays to our natural inductive ability to process unstructured data and spot generalisable patterns. We can always use these as inputs to be tested deductively in further analyses or even in experiments. Or even as inputs to an abductive design process.

These are early days for big data. Knowing only a little about the divide between our cognitive and affective abilities, I can’t but help thinking that the future of big data lies not with improving our cognition, though it invariably plays a role, but in improving our pattern recognition. Not in just reinforcing deductive logic, but in feeding our inductive and abductive logic systems. The systems that create brand new possibilities, rather than just improving the ones we already have.

Who do you want to see benefit from big data? The automaton with the pointy head sitting in eth corner patiently proving what you already knew? Or the designer creating wonderful new things that you didn’t even know you needed. Until you had them. Now where did I put my Apple iPad?

Graham Hill

Customer-centric Innovator

@grahamhill

Graham – Often the case, your responses are fun to consider and push my own thinking even further, for that I am appreciative.

I thoroughly enjoyed the beautiful mind, from many perspectives. For one, I did not know that my dad was invited to Wheeler labs, until I saw that movie. Nash ‘connected the dots’ (see previous post) my way of saying he saw patterns. Nash was able to see patterns that others do not see. The subject of this post is that the patterns are very hard to see for most people. Complex patterns are even harder. When the questions become too complex, then they are replaced by easier questions – but that is not always what is needed (my transition to the book).

I have been reading the book by Daniel Kahneman – ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’, studying specific sections in fact. The system one versus system two approach guided much of my thinking and why I tempered some of my own thoughts. You will also recognize some other examples from the book, such as the 1160 CFOs from major corporation who were asked to predict the trend of the S&P – there was a NEGATIVE correlation. In other words, almost all of them got it wrong. Here are the top (in theory) CFOs who trusted their gut (almost all of them) and got it wrong.

“Organizations that take the word of overconfident experts can expect costly consequences”

There is also the section where entrepreneurs who went forward basically on instinct, and were wrong almost 100% of the time (when the advice was to forget the idea, it is not viable). Further, what we read about in mainstream media are the exceptions not the rules. For every internet millionaire are a 100 also-rans. Talking of mainstream media, the book makes an excellent point; Truth sayers are frowned upon, those who speak with confidence and are positive are the ones who are listened to. Few people like the cynic – but we need more of them.

I believe that my post weighed the options and presented an objective view – look at the data, be a skeptic. Skepticism goes both ways. If you are normally a gut instinct person, your skepticism would be to find some data you trust and take a look. If you are ‘pointed hat in the corner type’ then add a bit of your gut to the analysis.

“confidence is valued over uncertainty…Experts who acknowledge the full extent of their ignorance may expect to be replaced by more confident competitors”

As for system one and system two, that is a great conversation. To me (and I believe the book discusses this point), instincts are really about the transition from system two to system one when you become a natural at something. Take driving for example – a mostly system one exercise….until you put me in the UK and place me on the wrong (other) side of the road, then it becomes system two. The fireman point made early in the book is what helped me to understand

BigData is going to make the problem domain harder, not easier – that is what my gut tells me anyway.

Hey Mitch and Graham,

Here’s my take. First, you touched on a whole bunch of elements of the data value question. So, I’m going to focus on one. I have to look at this issue from a practial point of view. So, as a practical intepretation of one of Graham’s comments.

To Graham’s point, the value of data rests in our ability to actually take it in a process it for the purpose of doing something with it.

Mitch, your first chart seems to indicate that there are people that would actually prefer to make decisions on intuition or gut feel. In my experience, I haven’t met a general business manager that wouldn’t prefer to at least have validating data points to support his gut feel. As a profession, sales people seem to be the most likely to operate on pure feel. But, even sales guys, given the option, would prefer to be right than wrong. Agree? So, my observational evidence suggest that the reasonable business person doesn’t shun the data as a prefered method of decision making. The issue lies in, as Graham said, the ability to actuall make sense of the data, even in its pre-processed form. But, even more to the point, it is the lack of confidence in the data that drives people to revert to intuition.

I am dealing with that very same challenge right now. When I get P&L data that changes from period to period, I don’t know what to trust. So, I’m forced to rely on other means of decision making. Not that it is my preference. But, the inaccuracy and inconsistency of the answers the data provide leave me no choice.

This is why the whole “more data more data” movement drives me nuts. The acquisition of social and other types of web data are cheap and easily accessable. But that doens’t mean its free. There is a cost to aggregate and analyze it, store it, manage it, etc. More is not always better. IMO organizations need to spead more time and resources on delivering actionable insights from the data they already possess rather than continuing on the quest to seek ever more volumes of data that may or may not produce a better, more reliable, accorate answer.

Thanks for letting me chime in

Barry

Barry,

Thanks for your thoughts, a great addition to the conversation. The charts are from sources who usually do some good work. My point is that according to their research, there are people (more than we would hope apparently) who are trusting their instincts and not looking closely enough at the data a bit scary.

In the book Graham and I both referenced the answer is to give a confidence interval of sorts. But, people do not like to, nor want to hear that, no matter if it is right or not. Like whether a new product will sell or how much it will sell. It is very hard to predict with accuracy, it should be an interval. I believe we need the computing engines to help get us closer and then we add our experience and domain knowledge on top of that.

For final point is spot on, and a great ‘insight’ 🙂

Thanks again,

Mitch

1. The danger in trusting your gut occurs when your gut differs from that of your customers. Think senior managers who make decisions about customers who are of different ages and backgrounds.

2. The danger in trusting the data occurs when the data is inaccurate. For example, Coke rolled out new Coke based on taste tastes. However, the data from those tests did not reflect their overall customer tastes preferences.

Conclusions: A. Therefore, never assume your data is accurate. Have a data integrity plan in place.Trust but verify.

B. Be prepared to demonstrate how your data analysis has contributed to successful decisions in order to overcome the doubters.

C. Any comment longer than 3 paragraphs that references stochastic calculus, John Nash, and uses the phrase, “cognitive and affective abilities,” is most likely written by Graham Hill (love ya, Graham:-)

Glenn Ross

(PS: I knew it was Graham before I finished the second paragraph.)